by Peter Timko

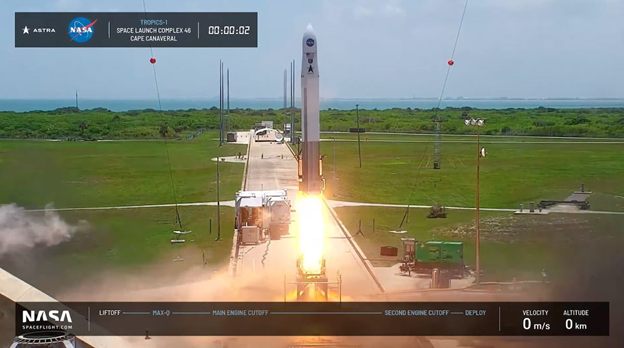

Back on June 12, Astra, an American launch company, attempted to deliver a payload into orbit. It did not go as planned. While the rocket successfully discharged its first stage of boosters, the second stage engine shut down prematurely. As a result, the vehicle, along with the two multi-million dollar weather satellites it was carrying for NASA, came crashing back down to Earth somewhere over the Atlantic. Such an outcome is generally regarded as a failure. In the coming days and weeks, engineers will probably find all sorts of fascinating technical reasons the rocket failed. However, as an anthropologist, I’m more interested in how such a failure works on a social level.

Failures, disasters, calamities, or as they’re sometimes euphemistically called, “anomalies” have been an integral part of space operations from the beginning. Throughout the 50s and 60s, both the US and Soviet space programs saw numerous rockets detonate on the launch pad. While both states did their best to downplay any missteps, by the Apollo era “things going horribly wrong” was a firmly established aspect of astronautics. In fact, the specter of disaster was so present that the Nixon administration prepared a brief speech to be delivered in the event that the Apollo 11 astronauts could not return home. This macabre bit of anticipation work even dictates the proper “burial” procedure to be followed by clergymen back on Earth.

Luckily, there was never a need for Nixon’s mournful address. Though, it’s worth considering that the text itself doesn’t focus so much on the failure aspect of leaving three men on the moon. Rather, and understandably so, the eulogy emphasizes bravery and sacrifice. It even suggests that having three people die on the lunar surface is, in some ways, a victory all its own: “For every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.” It’s not hard to imagine that such a framing could turn this particular fiasco into a galvanizing moment. Consider the aftermath of the Apollo 13 crisis just a few months later. According to some, the deft handling of this mission gone wrong “not only bolstered NASA’s image, but it also may have helped to gain crucial public and congressional support for continued manned space exploration,” (Kauffman, 2001).

Still, circumstances have changed. Companies like Astra can’t easily paper over failure with nationalistic tropes or a sentimental ode to humanity’s ambition. Really, they can’t even fall back on simple appeals as to the difficulty of launch mechanics—the common cliche “space is hard” now reads a bit as an excuse. Moreover, Astra must face the realities of a marketized space economy where value depends on things going right predictably and consistently. As many space industry workers have told me in interviews, any company hoping to secure future investment and contracts must demonstrate “launch heritage,” or a record of successful orbital deliveries.

With so much at stake, it’s interesting to see how the fallout of a launch failure operates in real time. Twitter, the preferred social medium for many space watchers, provides a window into how failure is received, massaged, or even celebrated (Bertrand et al, 2015). Looking at the fallout of this most recent event, one of the most salient trends is an explicit focus on financial repercussions. As soon as the news broke, feeds were full of riffing about how the market would digest such a failure and what it means for the company’s future. Many users wasted no time on speculating about the value of Astra’s stock—and unsurprisingly, $ASTR took a massive hit. Within a day, the price had dropped more than 25%.

I am sure failure comes with a cost. Will this company have the cash to withstand any additional failures? Will they run out of resources before they get it right?

— saywhatonemoretime (@CpaKenn) June 12, 2022

$ASTR 🤮🤮🤮 pic.twitter.com/GRSLynpqOx

— いか爺🇺🇸 $ABUS テンバガーに賭ける🚀🚀🚀 (@ikapapaETF) June 13, 2022

The market isn't even open right now, so these numbers are probably only going to get worse, but if you invested $1500 in $ASTR immediately after the stock went public...

— Lavie is tired 🏳️⚧️ (@lavie154) June 12, 2022

you would have $195 today.

at this point i wouldn't be surprised if this is how Astra's next launch goes pic.twitter.com/pzIkr0UjIq

— Nick 🚀✈️📸 (@_AstroGuy_) June 12, 2022

For some, this technical snafu and the resulting financial setback was amusing. Twitter has a reputation for being one of the more anti-social social networks, so some degree of mean spirited gloating is expected. Though, interestingly, many users began cracking jokes about “buying the dip,” an old investment bromide which cryptocurrency investors have adopted as semi-ironic refrain when things go wrong. This is less an endorsement of Astra’s ability to bounce back and more a tacit acknowledgement that for many space is all about the money—while watching humanity strive for the stars is all well and good, the real giant leaps will hopefully happen on the stock ticker.

A real shame for Astra. The tally for Rocket 3 now is only 2 successful launches out of a total 7 attempts (28% success).

— Matt Lowne (@Matt_Lowne) June 13, 2022

Hopefully each failure will help Astra improve the rocket and they'll get it flying reliably!

On the plus side, Astra stock is really cheap right now https://t.co/CGPfkN3vjr

But, this irreverent attitude wasn’t the only sentiment on display. Just as common were genuine words of support and encouragement, even from other launch companies. Astra’s timeline was filled with messages reminding the company that their efforts are not in vain: “I’m sure you’ll learn from this and better luck next time!” and “Every launch is a step closer to a successful orbit. Space is hard! Everyone at Astra should be proud” There were even a surprising number of very saccharine gifs. In contrast to the snark, these messages suggest that despite the overt competition present in the launch marketplace, many still just want to see space services succeed in general. As Valentine has pointed out in his studies of new space communities, it’s an industry with “remarkable solidarity across divisions,” (2016).

We've said it before and we'll say it again: failure is not an option, it comes standard in this industry — the key is to learn from it.

— Masten Space Systems (@mastenspace) March 7, 2022

Of course, in the grand scheme, this dud launch is nothing but a small blip. Astra will likely survive to launch another day. As observers have noted, new space companies are more open to slip-ups than their state counterparts. This is partially because this community has imported the tech industry’s more cavalier attitude toward error—for better or worse, Silicon Valley ideology is famously sanguine about faceplants and bungles (Daub, 2020). Though space is hard. There are surely other pitfalls ahead, and more serious ones at that. Satellites, while expensive, can be replaced. Human lives cannot. How would a privatized space industry metabolize a tragedy on the scale of the Challenger or Columbia accidents?

Moreover, the new space world is still fresh and its future uncertain. What happens when the failures are not isolated technical incidents, but large systemic shakeups? Economists have warned that sectors of the industry “exhibit the characteristics of a speculative bubble,” (Kim, 2018), and recent instability with major space SPACs also have insiders apprehensive. How will failure be received when it’s not a spectacular boom on a launchpad, but a disappointing bust on a balance sheet? Undoubtedly, those at the top and the largest companies will be alright, though the industry includes many younger, more precarious workers and more lofty, less grounded projects as well. How would such a setback affect their lives and these more eclectic imaginaries of a new, spacebound future?

- Bertrand, P. J., Niles, S. L., & Newman, D. J. (2015). Human Spaceflight in Social Media: Promoting Space Exploration Through Twitter. New Space, 3(2), 117-133.

- Daub, A. (2020). What tech calls thinking: An inquiry into the intellectual bedrock of Silicon Valley. FSG Originals.

- Kauffman, J. (2001). A successful failure: NASA’s crisis communications regarding Apollo 13. Public Relations Review, 27(4), 437-448.

- Valentine, D. (2012). Exit strategy: Profit, cosmology, and the future of humans in space. Anthropological Quarterly, 1045-1067.